Trading Contexts

I decided to take up mentoring as a way to give back. I realized that when I was just getting out of college and starting out in my career, that there really wasn’t a lot of feedback loops available. Within the school system, you have a pretty regimented system of teach, test, and repeat. Ideally, you either learn and improve or fail out. But, all of that goes out the window the moment you graduate. You are now on more of a constant tight rope of ambiguity.

Hopefully, as a mentor, I could provide a sounding board and provide the context many do not receive in their early career. Almost everyone has to go through the professional development lessons on their own. Increasingly, I feel mentorship is simply a way of layering and exposing context that would not otherwise be available. A good mentor can make seemingly big problems reveal themselves as small and can help mentees recognize that the problems that seem small and are often ignored are actually more important.

So, to that end, I wanted to share at least one piece of context:

The answer is not the most important thing

It is a very academic approach to believe the answer is paramount. That there is a “right” answer, and absolutely no trade offs or compromises. In the working world, this never holds true. At the end of the meeting or the end of the day, the exact answer tends to be near the bottom of importance relative to all of the other variables that come into play.

First, there are multiple “right” answers that all come with their own pros and cons. Hearing and working through these answers takes time, patience, and most importantly, empathy. For example, time after time, when discussing coding or technical interviews, I hear candidates that immediately try to find the “right” answer, so they can finish the question and move on. However, most hiring managers I know don’t care at all about the “right” answer to the question. They want to know how you break up a problem – what assumptions you are making? Are you willing to be honest about things you don’t know? All of these traits are more important to getting hired than whether or not the answer was the 100% correct one. Keep in mind, almost everyone out there would rather work with someone who is forthright, communicative, and looks at all the answers over someone who is “right” all the time.

Second, the relationships you maintain with your colleagues are going to survive long past that single answer. To ignore other’s perspectives, or force your approach onto your teammates is just going to make you an asshole. So, even if you pressure everyone around you into accepting your ‘answer’, you’ll be paying for it with damaged trust throughout the rest of your time on that team and with that employer. Sometimes, fighting for the proper version of cornflower blue just isn’t worth it. And arguably, if you are unable to communicate a compelling set of reasons why your set of trade offs is better than someone else’s, then it may be best to learn how to do that first by learning how to make a clear, concise and gentle argument. Once again, I’d rather work with someone who provides answers that can live alongside other answers to drive the best result possible.

Show your work. I had a algebra teacher that consistently tried to drill in me that I would get partial credit for wrong answers if I just took the time and effort to show how I derived my answer. But of course, I was a lazy junior high student who felt it was better to do all the work in my head. I never really took the advice to heart until much later, and I missed a lot of easy questions because of it. Showing, documenting, or laying out your work clearly is more an exercise for your peers to follow along than it is for you. What assumptions did you make? What data did you collect? What tests did you perform? At the end of the day, month, or year, your answer may be “right” or your answer may be “wrong”. The journey you took to get there is what could help hundreds of people in your footsteps to learn and grow from your journey – how you reached your conclusion. Once again, an answer is finite and time-boxed and of limited usefulness, helping people reach new conclusions pays dividends long after you’re gone and leaves your workplace a better place than when you arrived. Show your work.

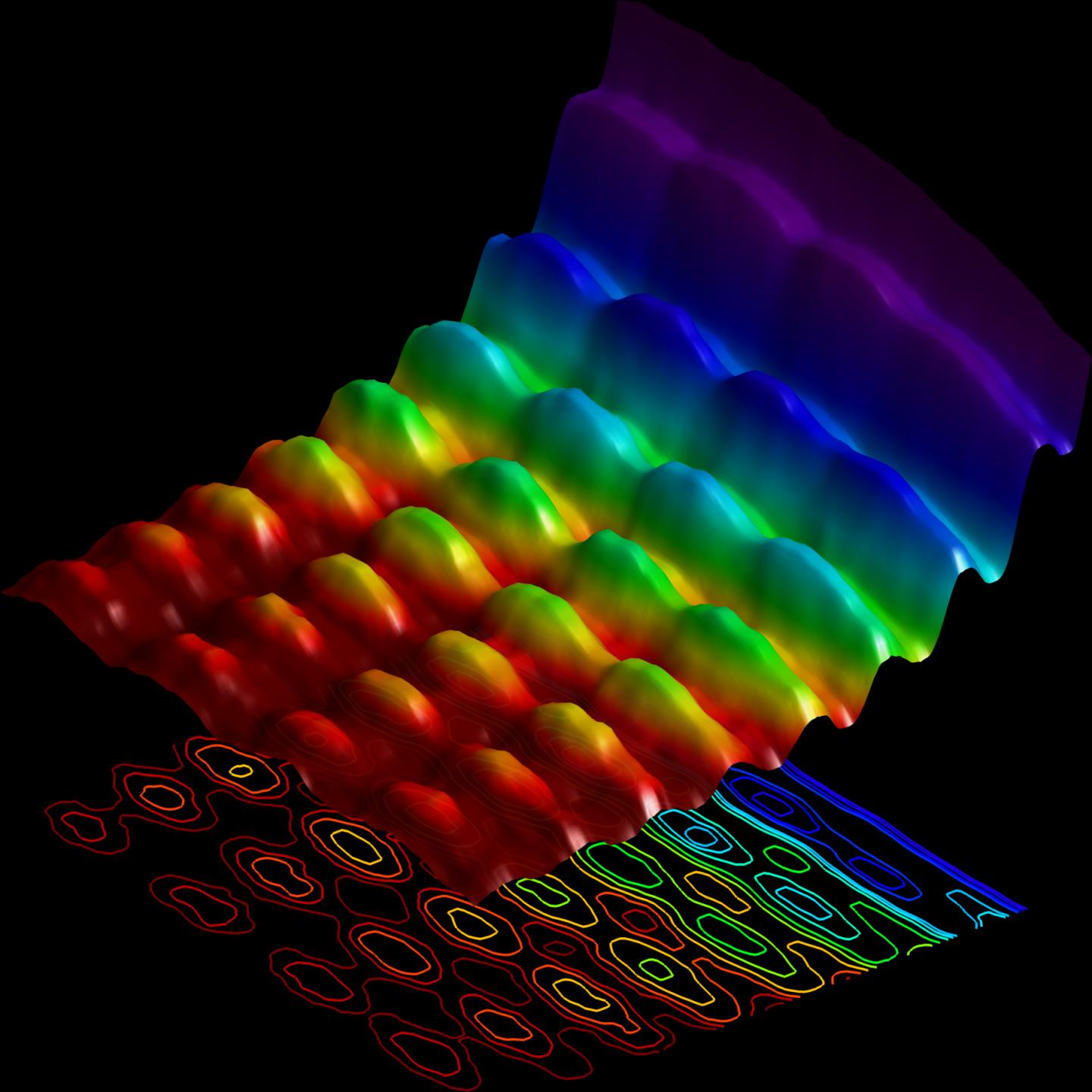

At the end of the day, it makes intuitive sense to try and over-value the answer. That is the process we learn in school, and it is a very human need to want to be “right”. “Right” answers make us feel good. But another way to think of it may be like an athlete. A runner is not running for the destination. They’ll get there, and it’ll feel great to arrive. But, they are a runner for the entire experience of running, for the stress and runner’s high that comes with the flow of feeling your feet hit the pavement, the wind through your hair, the soundtrack in your ears, and the slow and steady pulse of your heartbeat. Success in your career and your life is about the wave of discovery, application and reinvention more so than any one “right” answer.

To close with a physics metaphor, success is not found in the one-off particle of an answer, but in the motion of constant discovery and application. It is not a particle, but a wave.